An Introduction to Python

In this lesson we will learn how to work with arthritis inflammation datasets in Python. However, before we discuss how to deal with many data points, let’s learn how to work with single data values.

Variables

Any Python interpreter can be used as a calculator:

3 + 5 * 4

23

This is great but not very interesting. To do anything useful with data, we need

to assign its value to a variable. In Python, we can assign a value to a

variable, using the equals sign =. For example, to assign value 60 to a

variable weight_kg, we would execute:

weight_kg = 60

From now on, whenever we use weight_kg, Python will substitute the value we assigned to

it. In essence, a variable is just a name for a value.

In Python, variable names:

- can include letters, digits, and underscores

- cannot start with a digit

- are case sensitive.

This means that, for example:

weight0is a valid variable name, whereas0weightis notweightandWeightare different variables

Types of data

Python knows various types of data. Three common ones are:

- integer numbers

- floating point numbers, and

- strings.

In the example above, variable weight_kg has an integer value of 60.

To create a variable with a floating point value, we can execute:

weight_kg = 60.0

And to create a string we simply have to add single or double quotes around some text, for example:

weight_kg_text = 'weight in kilograms:'

Using Variables in Python

To display the value of a variable to the screen in Python, we can use the print function:

print(weight_kg)

60.0

We can display multiple things at once using only one print command:

print(weight_kg_text, weight_kg)

weight in kilograms: 60.0

Moreover, we can do arithmetics with variables right inside the print function:

print('weight in pounds:', 2.2 * weight_kg)

weight in pounds: 132.0

The above command, however, did not change the value of weight_kg:

print(weight_kg)

60.0

To change the value of the weight_kg variable, we have to

assign weight_kg a new value using the equals = sign:

weight_kg = 65.0

print('weight in kilograms is now:', weight_kg)

weight in kilograms is now: 65.0

Variables as Sticky Notes

A variable is analogous to a sticky note with a name written on it:

assigning a value to a variable is like putting that sticky note on a particular value.

This means that assigning a value to one variable does not change the values of other variables. For example, let’s store the subject’s weight in pounds in its own variable:

# There are 2.2 pounds per kilogram

weight_lb = 2.2 * weight_kg

print(weight_kg_text, weight_kg, 'and in pounds:', weight_lb)

weight in kilograms: 65.0 and in pounds: 143.0

Let’s now change

weight_kg:

weight_kg = 100.0

print('weight in kilograms is now:', weight_kg, 'and weight in pounds is still:', weight_lb)

weight in kilograms is now: 100.0 and weight in pounds is still: 143.0

Since weight_lb doesn’t remember where its value came from,

it isn’t automatically updated when weight_kg changes.

Words are useful, but what’s more useful are the sentences and stories we build with them. Similarly, while a lot of powerful, general tools are built into languages like Python, specialized tools built up from these basic units live in libraries that can be called upon when needed.

Loading data into Python

In order to load our inflammation data, we need to access (import in Python terminology) a library called NumPy. In general you should use this library if you want to do fancy things with numbers, especially if you have matrices or arrays. We can import NumPy using:

import numpy

Importing a library is like getting a piece of lab equipment out of a storage locker and setting it up on the bench. Libraries provide additional functionality to the basic Python package, much like a new piece of equipment adds functionality to a lab space. Just like in the lab, importing too many libraries can sometimes complicate and slow down your programs - so we only import what we need for each program. Once we’ve imported the library, we can ask the library to read our data file for us:

numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

array([[0., 0., 1., ..., 3., 0., 0.],

[0., 1., 2., ..., 1., 0., 1.],

[0., 1., 1., ..., 2., 1., 1.],

...,

[0., 1., 1., ..., 1., 1., 1.],

[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 2., 0.],

[0., 0., 1., ..., 1., 1., 0.]])

The expression numpy.loadtxt(...) is a function call that asks Python to run

the function loadtxt which belongs to the numpy library. This dotted

notation is used everywhere in Python: the thing that appears before the dot

contains the thing that appears after.

As an example, John Smith is the John that belongs to the Smith family. We could

use the dot notation to write his name smith.john, just as loadtxt is a

function that belongs to the numpy library.

numpy.loadtxt has two parameters: the name of the file we want to read and the

delimiter that separates values on a line. These both need to be character

strings (or strings for short), so we put them in quotes.

Since we haven’t told it to do anything else with the function’s output,

the notebook displays it.

In this case,

that output is the data we just loaded.

By default,

only a few rows and columns are shown

(with ... to omit elements when displaying big arrays). To save space, Python

displays numbers as 1. instead of 1.0

when there’s nothing interesting after the decimal point.

Our call to numpy.loadtxt read our file

but didn’t save the data in memory.

To do that,

we need to assign the array to a variable. Just as we can assign a single value to a variable, we

can also assign an array of values to a variable using the same syntax. Let’s re-run

numpy.loadtxt and save the returned data:

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

If we want to check that the data have been loaded, we can print the variable’s value:

print(data)

[[0. 0. 1. ... 3. 0. 0.]

[0. 1. 2. ... 1. 0. 1.]

[0. 1. 1. ... 2. 1. 1.]

...

[0. 1. 1. ... 1. 1. 1.]

[0. 0. 0. ... 0. 2. 0.]

[0. 0. 1. ... 1. 1. 0.]]

Now that the data are in memory,

we can manipulate them.

First,

let’s ask what type of thing data refers to:

print(type(data))

<class 'numpy.ndarray'>

The output tells us that data currently refers to

an N-dimensional array, the functionality for which is provided by the NumPy library.

These data correspond to arthritis patients’ inflammation.

The rows are the individual patients, and the columns

are their daily inflammation measurements.

Data Type

A Numpy array contains one or more elements

of the same type. The type function will only tell you that

a variable is a NumPy array but won't tell you the type of

thing inside the array.

We can find out the type

of the data contained in the NumPy array.

print(data.dtype)

dtype('float64')

This tells us that the NumPy array's elements are floating-point numbers.

With the following command, we can see the array’s shape:

print(data.shape)

(60, 40)

The output tells us that the data array variable contains 60 rows and 40 columns. When we

created the variable data to store our arthritis data, we didn’t just create the array; we also

created information about the array, called members or

attributes. This extra information describes data in the same way an adjective describes a noun.

data.shape is an attribute of data which describes the dimensions of data. We use the same

dotted notation for the attributes of variables that we use for the functions in libraries because

they have the same part-and-whole relationship.

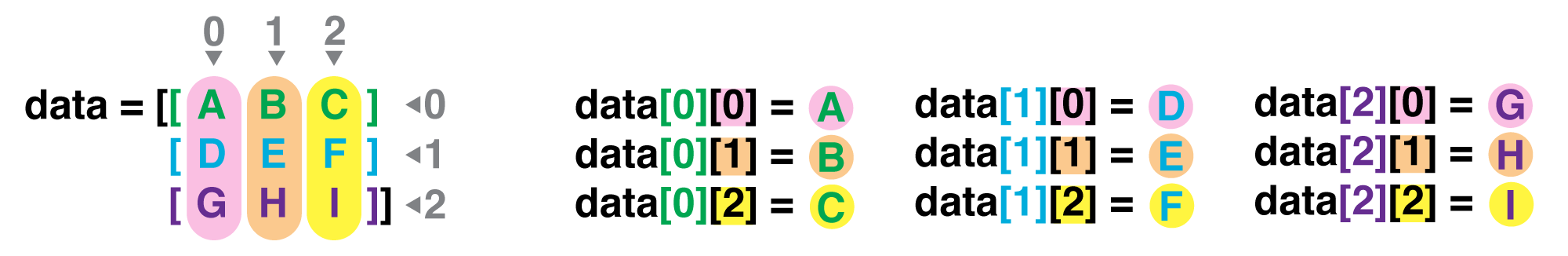

If we want to get a single number from the array, we must provide an index in square brackets after the variable name, just as we do in math when referring to an element of a matrix. Our inflammation data has two dimensions, so we will need to use two indices to refer to one specific value:

print('first value in data:', data[0, 0])

first value in data: 0.0

print('middle value in data:', data[30, 20])

middle value in data: 13.0

print(data[0:4, 0:10])

[[0. 0. 1. 3. 1. 2. 4. 7. 8. 3.]

[0. 1. 2. 1. 2. 1. 3. 2. 2. 6.]

[0. 1. 1. 3. 3. 2. 6. 2. 5. 9.]

[0. 0. 2. 0. 4. 2. 2. 1. 6. 7.]]

The expression data[30, 20] accesses the element at row 30, column 20. While this expression may

not surprise you,

data[0, 0] might.

Programming languages like Fortran, MATLAB and R start counting at 1

because that’s what human beings have done for thousands of years.

Languages in the C family (including C++, Java, Perl, and Python) count from 0

because it represents an offset from the first value in the array (the second

value is offset by one index from the first value). This is closer to the way

that computers represent arrays (if you are interested in the historical

reasons behind counting indices from zero, you can read

Mike Hoye’s blog post).

As a result,

if we have an M×N array in Python,

its indices go from 0 to M-1 on the first axis

and 0 to N-1 on the second.

It takes a bit of getting used to,

but one way to remember the rule is that

the index is how many steps we have to take from the start to get the item we want.

In the Corner

What may also surprise you is that when Python displays an array,

it shows the element with index [0, 0] in the upper left corner

rather than the lower left.

This is consistent with the way mathematicians draw matrices

but different from the Cartesian coordinates.

The indices are (row, column) instead of (column, row) for the same reason,

which can be confusing when plotting data.

Slicing data

An index like [30, 20] selects a single element of an array,

but we can select whole sections as well.

For example,

we can select the first ten days (columns) of values

for the first four patients (rows) like this:

The slice 0:4 means, “Start at index 0 and go up to, but not

including, index 4.”Again, the up-to-but-not-including takes a bit of getting used to, but the

rule is that the difference between the upper and lower bounds is the number of values in the slice.

We don’t have to start slices at 0:

print(data[5:10, 0:10])

[[0. 0. 1. 2. 2. 4. 2. 1. 6. 4.]

[0. 0. 2. 2. 4. 2. 2. 5. 5. 8.]

[0. 0. 1. 2. 3. 1. 2. 3. 5. 3.]

[0. 0. 0. 3. 1. 5. 6. 5. 5. 8.]

[0. 1. 1. 2. 1. 3. 5. 3. 5. 8.]]

We also don’t have to include the upper and lower bound on the slice. If we don’t include the lower bound, Python uses 0 by default; if we don’t include the upper, the slice runs to the end of the axis, and if we don’t include either (i.e., if we just use ‘:’ on its own), the slice includes everything:

small = data[:3, 36:]

print('small is:')

print(small)

small is:

[[2. 3. 0. 0.]

[1. 1. 0. 1.]

[2. 2. 1. 1.]]

The above example selects rows 0 through 2 and columns 36 through to the end of the array.

Arrays also know how to perform common mathematical operations on their values. The simplest operations with data are arithmetic: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. When you do such operations on arrays, the operation is done element-by-element. Thus:

doubledata = data * 2.0

will create a new array doubledata

each element of which is twice the value of the corresponding element in data:

print('original:')

print(data[:3, 36:])

print('doubledata:')

print(doubledata[:3, 36:])

original:

[[2. 3. 0. 0.]

[1. 1. 0. 1.]

[2. 2. 1. 1.]]

doubledata:

[[4. 6. 0. 0.]

[2. 2. 0. 2.]

[4. 4. 2. 2.]]

If, instead of taking an array and doing arithmetic with a single value (as above), you did the arithmetic operation with another array of the same shape, the operation will be done on corresponding elements of the two arrays. Thus:

tripledata = doubledata + data

will give you an array where tripledata[0,0] will equal doubledata[0,0] plus data[0,0],

and so on for all other elements of the arrays.

print('tripledata:')

print(tripledata[:3, 36:])

tripledata:

[[6. 9. 0. 0.]

[3. 3. 0. 3.]

[6. 6. 3. 3.]]

Often, we want to do more than add, subtract, multiply, and divide array elements. NumPy knows how

to do more complex operations, too. If we want to find the average inflammation for all patients on

all days, for example, we can ask NumPy to compute data’s mean value:

print(numpy.mean(data))

6.14875

mean is a function that takes an array as an argument.

Not All Functions Have Input

Generally, a function uses inputs to produce outputs. However, some functions produce outputs without needing any input. For example, checking the current time doesn't require any input.

import time print(time.ctime())

'Sat Mar 26 13:07:33 2016'

For functions that don't take in any arguments,

we still need parentheses (())

to tell Python to go and do something for us.

NumPy has lots of useful functions that take an array as input. Let’s use three of those functions to get some descriptive values about the dataset. We’ll also use multiple assignment, a convenient Python feature that will enable us to do this all in one line.

maxval, minval, stdval = numpy.max(data), numpy.min(data), numpy.std(data)

print('maximum inflammation:', maxval)

print('minimum inflammation:', minval)

print('standard deviation:', stdval)

maximum inflammation: 20.0

minimum inflammation: 0.0

standard deviation: 4.613833197118566

Here we’ve assigned the return value from numpy.max(data) to the variable maxval, the value

from numpy.min(data) to minval, and so on.

Mystery Functions in IPython

How did we know what functions NumPy has and how to use them?

If you are working in the IPython/Jupyter Notebook, there is an easy way to find out.

If you type the name of something followed by a dot, then you can use tab completion

(e.g. type numpy. and then press tab)

to see a list of all functions and attributes that you can use. After selecting one, you

can also add a question mark (e.g. numpy.cumprod?), and IPython will return an

explanation of the method! This is the same as doing help(numpy.cumprod).

When analyzing data, though, we often want to look at variations in statistical values, such as the maximum inflammation per patient or the average inflammation per day. One way to do this is to create a new temporary array of the data we want, then ask it to do the calculation:

patient_0 = data[0, :] # 0 on the first axis (rows), everything on the second (columns)

print('maximum inflammation for patient 0:', patient_0.max())

maximum inflammation for patient 0: 18.0

Everything in a line of code following the ‘#’ symbol is a comment that is ignored by Python. Comments allow programmers to leave explanatory notes for other programmers or their future selves.

We don’t actually need to store the row in a variable of its own. Instead, we can combine the selection and the function call:

print('maximum inflammation for patient 2:', numpy.max(data[2, :]))

maximum inflammation for patient 2: 19.0

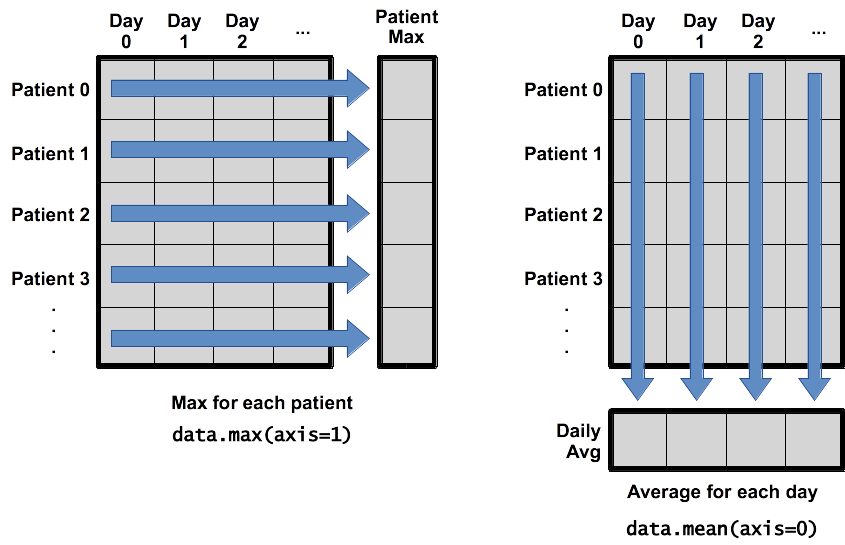

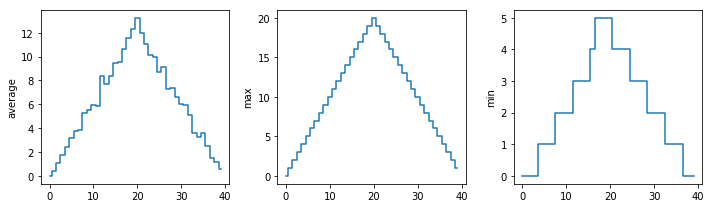

What if we need the maximum inflammation for each patient over all days (as in the next diagram on the left) or the average for each day (as in the diagram on the right)? As the diagram below shows, we want to perform the operation across an axis:

To support this functionality, most array functions allow us to specify the axis we want to work on. If we ask for the average across axis 0 (rows in our 2D example), we get:

print(numpy.mean(data, axis=0))

[ 0. 0.45 1.11666667 1.75 2.43333333 3.15

3.8 3.88333333 5.23333333 5.51666667 5.95 5.9

8.35 7.73333333 8.36666667 9.5 9.58333333 10.63333333

11.56666667 12.35 13.25 11.96666667 11.03333333 10.16666667

10. 8.66666667 9.15 7.25 7.33333333 6.58333333

6.06666667 5.95 5.11666667 3.6 3.3 3.56666667

2.48333333 1.5 1.13333333 0.56666667]

As a quick check, we can ask this array what its shape is:

print(numpy.mean(data, axis=0).shape)

(40,)

The expression (40,) tells us we have an N×1 vector,

so this is the average inflammation per day for all patients.

If we average across axis 1 (columns in our 2D example), we get:

print(numpy.mean(data, axis=1))

[5.45 5.425 6.1 5.9 5.55 6.225 5.975 6.65 6.625 6.525 6.775 5.8

6.225 5.75 5.225 6.3 6.55 5.7 5.85 6.55 5.775 5.825 6.175 6.1

5.8 6.425 6.05 6.025 6.175 6.55 6.175 6.35 6.725 6.125 7.075 5.725

5.925 6.15 6.075 5.75 5.975 5.725 6.3 5.9 6.75 5.925 7.225 6.15

5.95 6.275 5.7 6.1 6.825 5.975 6.725 5.7 6.25 6.4 7.05 5.9 ]

which is the average inflammation per patient across all days.

Visualizing data

The mathematician Richard Hamming once said, “The purpose of computing is insight, not numbers,” and

the best way to develop insight is often to visualize data. Visualization deserves an entire

lecture of its own, but we can explore a few features of Python’s matplotlib library here. While

there is no official plotting library, matplotlib is the de facto standard. First, we will

import the pyplot module from matplotlib and use two of its functions to create and display a

heat map of our data:

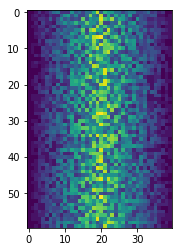

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot

image = matplotlib.pyplot.imshow(data)

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Blue pixels in this heat map represent low values, while yellow pixels represent high values. As we can see, inflammation rises and falls over a 40-day period.

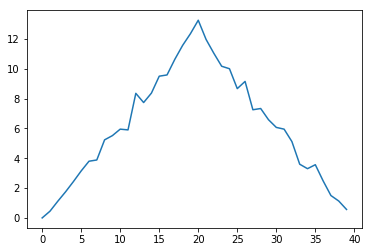

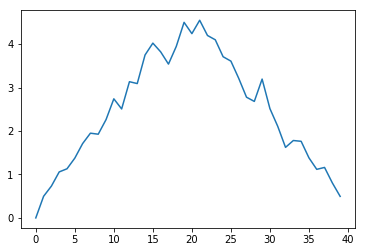

ave_inflammation = numpy.mean(data, axis=0)

ave_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(ave_inflammation)

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

Here, we have put the average per day across all patients in the variable ave_inflammation, then

asked matplotlib.pyplot to create and display a line graph of those values. The result is a

roughly linear rise and fall, which is suspicious: we might instead expect a sharper rise and slower

fall. Let’s have a look at two other statistics:

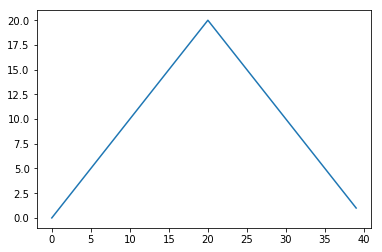

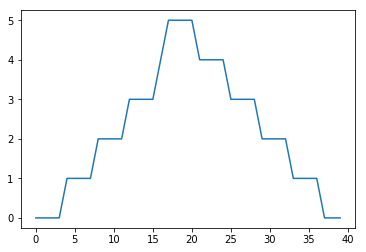

max_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0))

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

min_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0))

matplotlib.pyplot.show()

The maximum value rises and falls smoothly, while the minimum seems to be a step function. Neither trend seems particularly likely, so either there’s a mistake in our calculations or something is wrong with our data. This insight would have been difficult to reach by examining the numbers themselves without visualization tools.

Scientists Dislike Typing

We have just been importing NumPy and matplotlib using import numpy and import matplotlib.pyplot.

From here on we are going to shorten these imports, you can either adopt this or continue using the long version. The reason we are going to start using the shortened versions is that that is the way that the majority of open source scientific python libraries use these imports, so we want to get you used to them now.

When working with other people, it is important to agree on a convention of how common libraries are imported.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

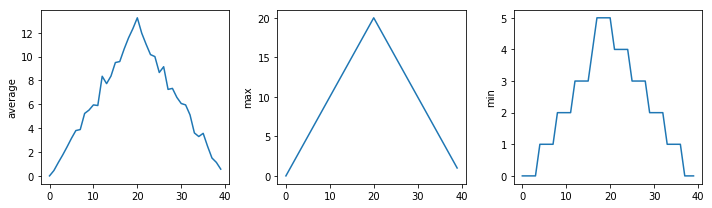

Grouping plots

You can group similar plots in a single figure using subplots.

This script below uses a number of new commands. The function plt.figure()

creates a space into which we will place all of our plots. The parameter figsize

tells Python how big to make this space. Each subplot is placed into the figure using

its add_subplot method. The add_subplot method takes 3

parameters. The first denotes how many total rows of subplots there are, the second parameter

refers to the total number of subplot columns, and the final parameter denotes which subplot

your variable is referencing (left-to-right, top-to-bottom). Each subplot is stored in a

different variable (axes1, axes2, axes3). Once a subplot is created, the axes can

be titled using the set_xlabel() command (or set_ylabel()).

Here are our three plots side by side:

data = np.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10.0, 3.0))

axes1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 1)

axes2 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 2)

axes3 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 3)

axes1.set_ylabel('average')

axes1.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0))

axes2.set_ylabel('max')

axes2.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0))

axes3.set_ylabel('min')

axes3.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0))

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()

The call to loadtxt reads our data,

and the rest of the program tells the plotting library

how large we want the figure to be,

that we’re creating three subplots,

what to draw for each one,

and that we want a tight layout.

(If we leave out that call to fig.tight_layout(),

the graphs will actually be squeezed together more closely.)

Challenge: Check Your Understanding

What values do the variables mass and age have after each statement in the following program?

Test your answers by executing the commands.

mass = 47.5 age = 122 mass = mass * 2.0 age = age - 20

Challenge: Sorting Out References

What does the following program print out?

first, second = 'Grace', 'Hopper' third, fourth = second, first print(third, fourth)

Solution

Hopper Grace

Challenge: Slicing Strings

A section of an array is called a slice. We can take slices of character strings as well:

element = 'oxygen' print('first three characters:', element[0:3]) print('last three characters:', element[3:6])

first three characters: oxy last three characters: gen

What is the value of element[:4]?

What about element[4:]?

Or element[:]?

Solution

oxyg en oxygen

Challenge:

What is element[-1]?

What is element[-2]?

Solution

n e

Challenge:

Given those answers, explain what element[1:-1] does.

Solution

Creates a substring from index 1 up to (not including) the final index, effectively removing the first and last letters from 'oxygen'

Challenge: Thin Slices

The expression element[3:3] produces an empty string,

i.e., a string that contains no characters.

If data holds our array of patient data,

what does data[3:3, 4:4] produce?

What about data[3:3, :]?

Solution

[] []

Challenge: Plot Scaling

Why do all of our plots stop just short of the upper end of our graph?

Solution

Because matplotlib normally sets x and y axes limits to the min and max of our data (depending on data range)

If we want to change this, we can use the set_ylim(min, max) method of each 'axes',

for example:

axes3.set_ylim(0,6)

Challenge:

Update your plotting code to automatically set a more appropriate scale.

(Hint: you can make use of the max and min methods to help.)

Solution

# One method axes3.set_ylabel('min') axes3.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0)) axes3.set_ylim(0,6)

# A more automated approach min_data = numpy.min(data, axis=0) axes3.set_ylabel('min') axes3.plot(min_data) axes3.set_ylim(numpy.min(min_data), numpy.max(min_data) * 1.1)

Challenge: Drawing Straight Lines

In the center and right subplots above, we expect all lines to look like step functions because non-integer value are not realistic for the minimum and maximum values. However, you can see that the lines are not always vertical or horizontal, and in particular the step function in the subplot on the right looks slanted. Why is this?

Solution

Because matplotlib interpolates (draws a straight line) between the points.

One way to do avoid this is to use the Matplotlib drawstyle option:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10.0, 3.0))

axes1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 1)

axes2 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 2)

axes3 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 3)

axes1.set_ylabel('average')

axes1.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0), drawstyle='steps-mid')

axes2.set_ylabel('max')

axes2.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0), drawstyle='steps-mid')

axes3.set_ylabel('min')

axes3.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0), drawstyle='steps-mid')

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Challenge: Make Your Own Plot

Create a plot showing the standard deviation (numpy.std)

of the inflammation data for each day across all patients.

Solution

std_plot = plt.plot(numpy.std(data, axis=0))

plt.show()

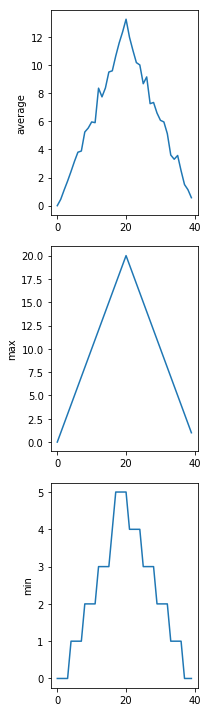

Challenge: Moving Plots Around

Modify the program to display the three plots on top of one another instead of side by side.

Solution

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

# change figsize (swap width and height)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(3.0, 10.0))

# change add_subplot (swap first two parameters)

axes1 = fig.add_subplot(3, 1, 1)

axes2 = fig.add_subplot(3, 1, 2)

axes3 = fig.add_subplot(3, 1, 3)

axes1.set_ylabel('average')

axes1.plot(numpy.mean(data, axis=0))

axes2.set_ylabel('max')

axes2.plot(numpy.max(data, axis=0))

axes3.set_ylabel('min')

axes3.plot(numpy.min(data, axis=0))

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Stacking Arrays

Arrays can be concatenated and stacked on top of one another,

using NumPy’s vstack and hstack functions for vertical and horizontal stacking, respectively.

import numpy as np

A = numpy.array([[1,2,3], [4,5,6], [7, 8, 9]])

print('A = ')

print(A)

B = numpy.hstack([A, A])

print('B = ')

print(B)

C = numpy.vstack([A, A])

print('C = ')

print(C)

A =

[[1 2 3]

[4 5 6]

[7 8 9]]

B =

[[1 2 3 1 2 3]

[4 5 6 4 5 6]

[7 8 9 7 8 9]]

C =

[[1 2 3]

[4 5 6]

[7 8 9]

[1 2 3]

[4 5 6]

[7 8 9]]

Challenge:

Write some additional code that slices the first and last columns of A,

and stacks them into a 3x2 array.

Make sure to print the results to verify your solution.

Solution

A 'gotcha' with array indexing is that singleton dimensions

are dropped by default. That means A[:, 0] is a one dimensional

array, which won't stack as desired. To preserve singleton dimensions,

the index itself can be a slice or array. For example, A[:, :1] returns

a two dimensional array with one singleton dimension (i.e. a column

vector).

D = np.hstack((A[:, :1], A[:, -1:]))

print('D = ')

print(D)

D =

[[1 3]

[4 6]

[7 9]]

Solution

An alternative way to achieve the same result is to use Numpy's delete function to remove the second column of A.

D = np.delete(A, 1, 1)

print('D = ')

print(D)

D =

[[1 3]

[4 6]

[7 9]]

Change In Inflammation

This patient data is longitudinal in the sense that each row represents a series of observations relating to one individual. This means that the change in inflammation over time is a meaningful concept.

The numpy.diff() function takes a NumPy array and returns the

differences between two successive values along a specified axis. For

example, a NumPy array that looks like this:

npdiff = numpy.array([ 0, 2, 5, 9, 14])

Calling numpy.diff(npdiff) would do the following calculations and

put the answers in another array.

[ 2 - 0, 5 - 2, 9 - 5, 14 - 9 ]

numpy.diff(npdiff)

array([2, 3, 4, 5])

Challenge:

Which axis would it make sense to use this function along?

Solution

Since the row axis (0) is patients, it does not make sense to get the difference between two arbitrary patients. The column axis (1) is in days, so the difference is the change in inflammation -- a meaningful concept.

numpy.diff(data, axis=1)

array([[ 0., 1., 2., ..., 1., -3., 0.],

[ 1., 1., -1., ..., 0., -1., 1.],

[ 1., 0., 2., ..., 0., -1., 0.],

...,

[ 1., 0., 0., ..., -1., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 1., ..., -2., 2., -2.],

[ 0., 1., -1., ..., -2., 0., -1.]])

Challenge:

If the shape of an individual data file is (60, 40) (60 rows and 40

columns), what would the shape of the array be after you run the diff()

function and why?

Solution

The shape will be (60, 39) because there is one fewer difference between

columns than there are columns in the data.

Challenge:

How would you find the largest change in inflammation for each patient? Does it matter if the change in inflammation is an increase or a decrease?

Solution

By using the numpy.max() function after you apply the numpy.diff()

function, you will get the largest difference between days.

numpy.max(numpy.diff(data, axis=1), axis=1)

array([ 7., 12., 11., 10., 11., 13., 10., 8., 10., 10., 7., 7., 13.,

7., 10., 10., 8., 10., 9., 10., 13., 7., 12., 9., 12., 11.,

10., 10., 7., 10., 11., 10., 8., 11., 12., 10., 9., 10., 13.,

10., 7., 7., 10., 13., 12., 8., 8., 10., 10., 9., 8., 13.,

10., 7., 10., 8., 12., 10., 7., 12.])

Challenge:

If inflammation values decrease along an axis, then the difference from

one element to the next will be negative. If

you are interested in the magnitude of the change and not the

direction, the numpy.absolute() function will provide that.

Notice the difference if you get the largest absolute difference

between readings.

numpy.max(numpy.absolute(numpy.diff(data, axis=1)), axis=1)

array([12., 14., 11., 13., 11., 13., 10., 12., 10., 10., 10., 12., 13.,

10., 11., 10., 12., 13., 9., 10., 13., 9., 12., 9., 12., 11.,

10., 13., 9., 13., 11., 11., 8., 11., 12., 13., 9., 10., 13.,

11., 11., 13., 11., 13., 13., 10., 9., 10., 10., 9., 9., 13.,

10., 9., 10., 11., 13., 10., 10., 12.])

The material in this notebook is derived from the Software Carpentry lessons © Software Carpentry under the terms of the CC-BY 4.0 license.